Hey there, BunnyGang!

It often seems unfair that some of the sweetest and cutest animals are also some of the most vulnerable to predation or illness. Perhaps our feelings of protectiveness over these animals is related to their vulnerability, or maybe their perceived “cuteness” has played some kind of evolutionary role in their preservation and longevity. We’re not sure.

What we do know is that rabbits face a number of serious threats in terms of natural predators, as well as susceptibility to a long list of nasty health issues and illnesses. Today’s subject relates to an invasive combination of both of these threats, though the predators we’re discussing can often be hard to see.

Myxomatosis is a highly contagious viral disease that affects rabbits by causing edema and discharge from the eyes, nose, and anogenital region of those infected. The Myxoma virus, which is a version of poxvirus (Poxviridae), is highly contagious and often leads to severe illness or death in infected rabbits. Here are some key points to know about myxomatosis in rabbits:

-

Transmission: Myxomatosis is primarily transmitted through small, biting parasites, especially fleas and mosquitoes. These parasites can quickly carry the virus from infected rabbits to healthy ones, leading to the spread of the disease within a population.

-

Symptoms: Infected rabbits typically exhibit a range of symptoms, including swollen and puffy eyelids, conjunctivitis, nasal discharge, lethargy, loss of appetite, fever, and skin lesions. These lesions can become severe, leading to the formation of lumps or nodules on various parts of the body, including the head, ears, and genital areas.

-

Progression: Myxomatosis progresses rapidly, and affected rabbits may become severely debilitated within a few days. Secondary bacterial infections often occur due to the weakened immune system, further complicating the disease.

-

Survival Rate: The survival rate for rabbits with myxomatosis varies, but it is generally low. Some rabbits may recover with early detection and prompt veterinary treatment, but many succumb to the disease, especially in areas where the more virulent strains of the virus are present.

-

Prevention: Preventing myxomatosis involves protecting rabbits from exposure to infected fleas, mosquitos, or other parasites. This can include using insect screens on hutches or cages, controlling mosquito and flea populations, and vaccinating pet rabbits where appropriate. Vaccination is a common preventive measure, but it may not always provide complete protection, especially in areas with highly virulent strains of the virus.

-

Impact: Myxomatosis has been used as a biological control agent to manage wild rabbit populations in some regions where rabbits are considered pests. However, it has been controversial due to its often severe and painful effects on the infected animals.

It's essential for rabbit owners to be aware of myxomatosis, especially if they live in areas where the disease is prevalent. If a pet rabbit shows any symptoms of myxomatosis, seeking immediate veterinary care is the only chance for an infected rabbit’s survival. Additionally, taking preventive measures to reduce the risk of exposure to the virus is the best way to help protect pet rabbits from this deadly disease.

History of the Disease

The disease myxomatosis, caused by myxoma virus, was first recognized by a laboratory scientist in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1896. The virus is believed to have originated in the Tapeti or tropical forest rabbit, within whom the virus causes relatively mild disease.

This allowed the virus to become prevalent in a community, before mutating into more virulent and fatal strains. Transmission to other species of rabbits in neighboring areas, as well as from wild rabbits to domestic ones started occurring sometime after this as the disease spread throughout South America, almost certainly via mosquitos.

Myxomatosis was first recognized in North America in 1928 when natural outbreaks of the now potent and largely fatal disease started occurring in several rabbit colonies near San Diego, California.

It’s speculated that the virus that caused the first outbreaks in Southern California may have been introduced into the United States from Mexico through the importation of infected domestic rabbits from South American countries. Since its introduction to Southern California around 1928, the disease has become endemic in the western United States.

Shortly before making its way up to North America, or perhaps even occurring simultaneously, myxomatosis was first introduced in Australia in 1926, as a deliberate, human-engineered effort to control the outbreak of non-native species of rabbits that had begun proliferating and destabilizing the subcontinent’s ecosystem.

Although the virus was officially introduced in 1926, for more than two decades it was used only in controlled experimental studies. In 1950, the decision was made to release the virus into the wild rabbit population. After taking a couple of years to become established in the population, it then started to spread rapidly. By 1953, it had decimated Australia’s rabbit population.

The disease is now endemic in the wild rabbit population of Australia, where it occasionally assumes epidemic proportions. Within a decade of the disease’s intentional release into the rabbit population of Australia, a process of natural selection gave rise to rabbits with natural resistances to the myxoma virus.

In these rabbits, a virulent strain of myxoma caused only 25% mortality, compared to 90% mortality in non-resistant strains of rabbits. This dramatic shift in herd immunity quickly spread through the gene pool, and is likely responsible for the widespread resistance that modern wild rabbits in Australia have to virulent strains of the disease.

The deliberate introduction of myxomatosis into Europe followed the early effectiveness of the Australian campaign, though it took place through a clumsier and less methodical dissemination. In 1952, while French environmental officials were dilberating the pros and cons of introducing the disease, a private individual acquired the virus and released it on his own estate in an effort to control the rabbit population in his area.

The virus spread rapidly through the countryside, and by the end of 1953 myxomatosis had been diagnosed in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Luxembourg, Spain, and England. Myxomatosis is now endemic in rabbits in both South America, North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

The transmission site is usually the superficial layers of the skin, especially of the eyelids and at the base of the ears, where surface-feeding parasites are likely to feed.

Aside from fleas, mosquitos, and other biting parasites, the disease has been shown to be transmissible from physical contact by rabbit to rabbit, as well as through the talons of predatory birds and carrion feeders, who may play a role in the wider dissemination of the virus.

In an attempt to improve the effectiveness of myxomatosis in rabbit control, the European rabbit flea was (again, intentionally) introduced into Australia in 1966. The fleas reproduced quickly among the wild rabbit populations and, as a result, myxomatosis has become more prevalent in the drier tableland areas, shifting seasonal outbreaks from summer to spring.

The flea is also a more effective reservoir of the virus, having significantly longer lifespans than mosquitoes. The average mosquito lives only around 2 to 3 weeks, while fleas can remain active for about a year.

Mortality:

Myxoma viral infections among domestic rabbits often result in severe disease with a high rate of mortality.

In the acute form of disease, rabbits will survive for 1 to 2 weeks, typically with redness and puffiness of the eyes and eyelids, as well as increasing inflammation and edema around the anal, genital, oral, and nasal orifices. Skin hemorrhages and convulsions precede death on the ninth or tenth day.

Effects of the virus:

In addition to redness and puffiness of the eyes, visible tumors, nodules, and lesions on the skin, focal hemorrhages may be observed in skin, kidneys, lymph nodes, testes, heart, stomach, and intestines.

Degeneration and necrosis occur frequently in lymph nodes, pulmonary alveoli, spleen, and central veins of hepatic lobules. Stellate cells may occur in lymph nodes, bone marrow, uterus, ovaries, testes, and lungs

Controlling and Containing Myxomatosis

Control of myxomatosis is of prime importance in areas where the virus is endemic in wild rabbit populations. In such areas, vector control, including adequate screening to exclude mosquitoes, serves to keep the disease under control.

To prevent the risk of contagion, sick rabbits should be isolated, and measures must be taken to effectively contain any of the disease-carrying parasites that might remain.

Some vaccines have shown efficacy in producing an immunity to the disease for up to 9 months, which may be a useful option for groups of rabbits who have recently been exposed to an infected party, and treatment should be pursued immediately.

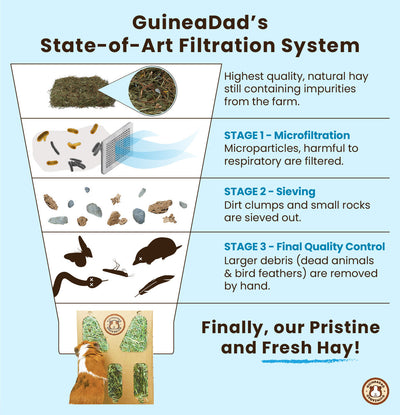

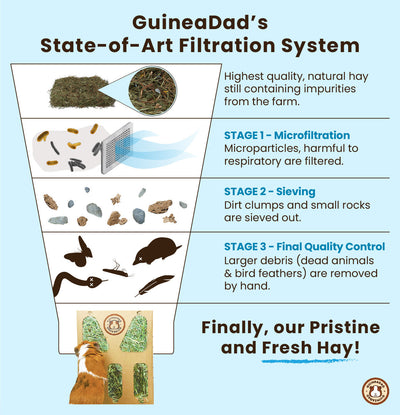

In addition to keeping your rabbit safe from mosquitos, fleas, and other parasites, one of the best ways to keep their immune system strong and resistant to infections is by providing them with clean, high-quality, microfiltered clean, high- quality, microfiltered hay. At GuineaDad, we do our very best to keep our furry friends healthy and living their best lives.

Stay safe out there, BunnyGang!

~ BunnyDad